EARLY HISTORY

Jackson Barracks was built in the 1830s under the Jackson Administration to house the Federal military garrison defending the city of New Orleans and the Lower Mississippi Valley. At the time, New Orleans was one of the wealthiest cities in the U.S. as the commerce of all lands west of the Allegheny Mountains was transported by steamboats and flatboats down the Mississippi River. The post was originally referred to as “The U.S. Barracks” or “The New Orleans Barracks.” It was rechristened in 1866 to honor Andrew Jackson, who was not only the Commander in Chief during its construction, but is a revered figure in the area for routing the British in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans.

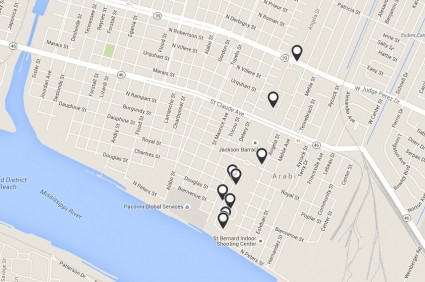

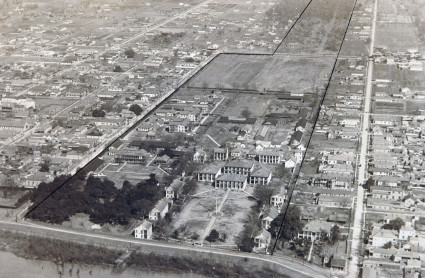

Louisiana Governor A.B. Roman wanted the post to be located in the city proper but a site downriver was selected by the military. Congress appropriated $180,000 for the new facility to be constructed about four miles downriver from the city – about a mile upriver from the site of Jackson’s victory. Built on a 300 foot by 900 foot track fronting the river, the post was designed to house four companies of infantry plus hospital and support facilities. The buildings were surrounded by a 12-foot high brick fence with round flank towers at each corner. Two of the original towers remain today and are used as distinguished visitor quarters.

The first troops to occupy the New Orleans Barracks were the Second Regiment of Dragoons commanded by Colonel David Twiggs, who later commanded the defense of New Orleans as a Confederate general in the Civil War. With the outbreak of the Second Seminole War in the 1830s, the Barracks served as an assembly area for troops being sent to fight in Florida. During the forced removal of the Seminoles to the Indian Territory– present day Oklahoma, New Orleans was a temporary stop on the migration west. Sick Native Americans received medical treatment at the Barracks hospital and some who died were buried on post.

THE CEMETERY

It is unknown how many people are buried here and who they were. The cemetery was in use from the post’s opening, in 1837, until the Civil War. In 1864 Chalmette National Cemetery was established by the occupying Union Army. All new military burials were at Chalmette and after 1866 many of the military burials interred at Jackson Barracks were reburied at Chalmette. The post cemetery was gradually abandoned and forgotten. Buildings went up on the site, leaving no visible signs of the burial grounds.

During the period of Indian Removal in the mid-19th century, thousands of Seminoles and Muscogee (Creek) Indians passed through New Orleans, forced from their homelands in Florida and Alabama to resettle in the Oklahoma Territory. Between 1837 and 1859, many of the tribal groups were confined at Jackson Barracks as they awaited transport up the Mississippi River by steamboat. Those who died at this way station were buried here, in the post cemetery, along with others who lived or were stationed at Jackson Barracks.

On January 17, 2005, a construction crew renovating a building on the site came across human remains. Archeologists determined that this was the original post cemetery and still held the remains of an unknown number of men and women. One of the two bodies accidentally uncovered in 2005 was a Seminole woman, who was identified through her tribal jewelry, the layers of bead necklaces and silver mementoes, commonly worn at the time. After the archeological investigations it was decided to leave all the burials undisturbed and establish a memorial green space to the memory of those who have been at rest here for more than 150 years.

View pictures of the historic markers here.

To visit the cemetery please contact the Jackson Barracks Museum 504-278-8024 or bev.a.boyko.nfg@mail.mil

MEXICAN WAR & THE BARRACKS’ HOSPITAL

As tension with Mexico grew, General Zachary Taylor was ordered to assemble an Army of Observation in Texas. Hostilities erupted in 1846 and the Barracks once again served as an assembly and embarkation point for volunteer militia and regular army troops being sent to Texas and Mexico. In January of 1847, the Army established the post as a general hospital to care for the sick and wounded troops returning from the war. An additional tract of land adjacent to the garrison was purchased that year for construction of a larger general hospital. Four spacious two-story wooden buildings surrounding a central courtyard were put up. In the center of the courtyard was an octagonal building, which served as a dispensary and an operating room. The Mexican War had ended by the time the hospital was completed, but the facility served thousands in the Civil War. During and after the Mexican War, several Army officers who passed through the Barracks would go on to gain fame as Presidents and Civil War generals, including Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, Louisiana-native P.G.T Beauregard, James Longstreet, George McClellan, and Robert E. Lee.

CIVIL WAR & RECONSTRUCTION

Louisiana seceded from the Union in 1861 and the Barracks was taken over by state militia troops. Confederate control was short lived as New Orleans fell to a Union naval force the following year. Under Union occupation, the Jackson Barracks hospital cared for thousands of troops during the war and Reconstruction. By the end of the century, the hospital had fallen into disrepair and was eventually demolished.

During Reconstruction (1865-1877), Jackson Barracks was home to several African American military units as continued political turbulence in the area required the presence of Federal Troops. The 25th Infantry Regiment, a regular army unit comprised of African American soldiers and officers, was formed at the Barracks in 1869. The 25th IR relocated to the western frontier where they gained fame as a contingent of the “Buffalo Soldiers.” During this period, Jackson Barracks administered control over small detachments stationed at the remote forts and defensive works around the city. In the summer, when yellow fever was a threat to the area, most military forces were withdrawn, leaving only a small caretaker force at the Barracks. The epidemic of 1878 struck the post along with the rest of the region, killing six of the fifteen men stationed there.

As the 19th century drew to a close, activity at Jackson Barracks again increased as America prepared for war with Spain. State artillery batteries, including the Louisiana Field Artillery, Washington Artillery, and the Donaldsonville Cannoneers trained on the post but were not deployed to the conflict.

A tradition dating from this period, largely forgotten today, is Jackson Barracks’ role in New Orleans Mardi Gras celebration. Rex, the King of Carnival, would send an order to the commandant to receive him. He would then arrive at the barracks by boat to be welcomed on the parade ground by a battalion of infantry and a regimental band. The post commander would formally hand over control of the city to Rex and then escort him into New Orleans to begin his reign over the festivities.

20TH CENTURY & WORLD WAR I

At the beginning of the 20th century, Jackson Barracks saw little drama but remained active as the War Department was modernizing America’s seacoast defenses. In 1912, a new river levee was constructed, necessitating the demolition of the original post headquarters and two of the guard towers. These are the only buildings from the original garrison that have been lost to date.

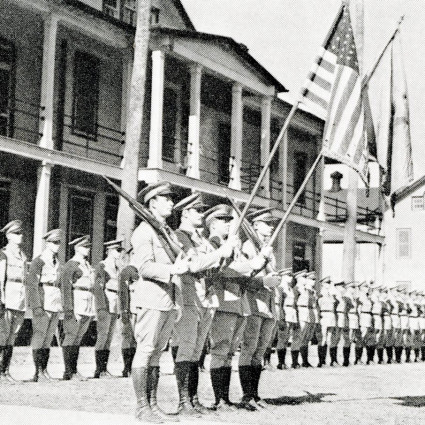

U.S. engagement in World War I turned Jackson Barracks into an active processing and training center. It was designated as headquarters of the Coast Defenses of New Orleans, South Atlantic Coast Artillery District. The burst of activity also brought more construction and an expansion of the post in 1918, as mess halls, horse stables, hospital facilities, troop quarters, and other buildings were erected. The 1st Trench Mortar Battalion, formed at Jackson Barracks and one of many units that trained on the grounds, participated in several engagements overseas, including the Meuse Argonne offensive. General John G. “Blackjack” Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force in France, conducted a postwar inspection of troops on Jackson Barracks original parade fields in 1920.

LOUISIANA NATIONAL GUARD MOVES IN

After WWI, Jackson Barracks was abandoned by the U.S. Army. It was saved from extinction, however, when the state requested that the post be turned over to the Louisiana National Guard. On February 1, 1922, the state took control of the installation with Jackson Barracks becoming the home of the famous Washington Artillery (141st Field Artillery) and the 108th Cavalry with their many horses. During this period, polo became a popular pastime on the grounds and attracted spectators from New Orleans. Leisure activity at the facility would decrease as the national and world economy declined rapidly at the end of the 1920s.

During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration sought to stimulate the economy by putting people to work and providing job-skills training. In 1936, Jackson Barracks was the recipient of a major restoration and new construction project that built a modern three story headquarters building (Fleming Hall), restored and updated the historic buildings, built new homes for the staff, constructed new cavalry facilities, and refurbished support facilities.

Prior to World War II, Jackson Barracks was the site for a Selective Service conference. General Raymond Fleming, the serving Louisiana Adjutant General and later Chief of the National Guard Bureau, was instrumental in developing the Selective Service plan, “the draft”, that would furnish the manpower for U.S. armed forces in World War II.

WORLD WAR II

As the U.S. entered the Second World War, New Orleans became a major port supporting the war effort throughout the Americas and in both theaters. Per the lease agreement between the U.S. Army and the Louisiana National Guard, most of Jackson Barracks reverted to the U.S. War Department’s control. It buzzed with activity as hundreds of military and civilian employees populated the post conducting support operations. The grounds and facilities were once again used as a processing center and point of embarkation. The Selective Service office was located in Fleming Hall. German and Italian prisoners of war were also detained on post. A few buildings remained under state control and the entire post was returned to Louisiana National Guard control after the war.

JACKSON BARRACKS TODAY

With the efforts of Major General O.J. Daigle, the Louisiana Adjutant General at the time, the architectural and historical significance of Jackson Barracks was recognized in 1976 when it was listed on the National Register as a historic district of national significance. With the exception of the original headquarters building and the two corner towers, the historic district retains its original antebellum layout and architectural integrity. Many believe Jackson Barracks has the finest collection of architecturally significant antebellum structures in the United States.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, severely flooding New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish. Jackson Barracks did not escape the storm’s wrath. Every building on the facility was flooded with water depths ranging from 3 feet at the levee to more than 18 feet at the northernmost part of the property. Entire houses from the Ninth Ward were lifted from their foundations and over the post’s security fences. Generators powered by natural gas failed as the underground gas lines were compromised. In its long history, the garrison had never faced adversity of these proportions. After riding out Katrina’s fury, the Guardsmen stationed at Jackson Barracks immediately took boats into the surrounding neighborhoods to rescue survivors from roofs and attics. Those civilians were eventually evacuated and the water drained, but every structure on Jackson Barracks was damaged or destroyed.

The Louisiana National Guard Headquarters was temporarily relocated to Camp Beauregard and Gillis W. Long Center. Under the leadership of Major General Bennett C. Landreneau, Adjutant General, a herculean effort to rebuild the Barracks was underway. Using congressionally appropriated funds and grants provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, a new master plan was created for the reconstruction of the historic facility. New readiness centers for the Joint Force Headquarters, the 141st Field Artillery (Washington Artillery), and the 139th Regional Support Group were designed and constructed, as well as the Adjutant General’s Headquarters. In addition to these structures, reconstruction continued on other support facilities, a multi-use museum complex, temporary lodging, and the historical housing on Jackson Barracks. The antebellum buildings of the original garrison were carefully restored and returned to their original function as residential housing. The new construction continues the architectural design and ambience of the historic garrison buildings, resulting in one of the most attractive National Guard installations in the nation.

Rededicated as Louisiana National Guard Headquarters on November 5, 2010, Jackson Barracks continues its tradition of serving the citizens of the state and the nation. For more than 175 years, the post has survived war, the ravages of time, flooding and severe hurricanes. As the headquarters for the Louisiana National Guard, it serves as an enduring monument to the citizen-soldier, the military, and our nation.